Information

Date: March 24 (Wed.) 2021, 14:00-16:00

Location: IEAT International Conference Center Meeting Room 1 (No. 350, Songjiang Road, Zhongshan District, Taipei City)

Moderator:

- Ken-Ying Tseng, partner, Lee and Li

Panelist:

- Dr. Xin-Wu Lin, vice president, Taiwan Institute of Economic Research

- Dr. Hung-Hao Chang, professor, Department of Agricultural Economics at National Taiwan University (NTU), former commissioner of Taiwan Fair Trade Committee

- Hui-Ju Tsai, Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication, Tamkang University

- Hao-chun Tai, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Intellectual Property and Communication Technology, Shih Hsin University

Session details

The European Commission published the proposal of Digital Markets Act (DMA) at the end of 2020. The DMA establishes a set of criteria for qualifying the so-called “gatekeeper” platforms with a set of obligations for the gatekeepers to comply in their daily operations. According to the EU commission, one of the main goals of DMA is to establish a level playing field to foster innovation, growth, and competitiveness, both in the European Single Market and globally. What exactly does DMA regulate? Is it the best solution for states to regulate Big Tech?

Minutes

The moderator started by explaining the original idea behind this panel discussion. She recalled that right after the Capitol riots in January, Parler, a Rightwing Twitter alternative, was removed from both Google and Apple app stores immediately, and then was completely shut down when Amazon (AWS) withdrew its cloud hosting services.

Supportive or not, the public was genuinely surprised by the speed and coordination with which Parler was taken down. Many civil liberties advocates called it the “private sector censorship” and argued that this was one of the main reasons why the Big Tech should be under stricter regulations.

About late last year, the EU Commission published the proposal of ‘the Digital Service Act Package.’ The package encompasses 2 sets of regulations, the Digital Service Act (DSA) and the Digital Market Act (DMA). The DMA establishes a set of criteria for qualifying the so-called “gatekeeper” platforms with a set of obligations for the gatekeepers to comply in their daily operations.

Some people linked the Parler incident to DMA, arguing that the latter is Europe’s another move—after the General Data Protection Regulation in 2018—to constrain the Big Tech. This kind of argument could be misleading. Today’s panel will start a brief introduction of the objective and content of DMA. After that, the panel will discuss the confusing and often misunderstood relationship between the Big Tach, monopoly, and antitrust regulations.

Dr. Xin-Wu Lin, vice president of Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, explained what exactly the DMA regulates. There are two possible solutions to maintain the market order. One is to examine the outcomes of actions (ex post), and the other is to define illegal practices upfront (ex ante).

According to the EU commission, the Digital Service Act Package has two main goals:

- To create a safer digital space in which the fundamental rights of all users of digital services are protected.

- To establish a level playing field to foster innovation, growth, and competitiveness, both in the European Single Market and globally.

The key element of the DMA is the concept of the ‘gatekeeper’ platforms. DMA sets out a set of narrowly defined objective criteria for qualifying a large online platform as a “gatekeeper”. In its webpage, the EU commission lays out the criteria; if a company:

- has a strong economic position, significant impact on the internal market and is active in multiple EU countries;

- has a strong intermediation position, meaning that it links a large user base to a large number of businesses;

- has (or is about to have) an entrenched and durable position in the market, meaning that it is stable over time;

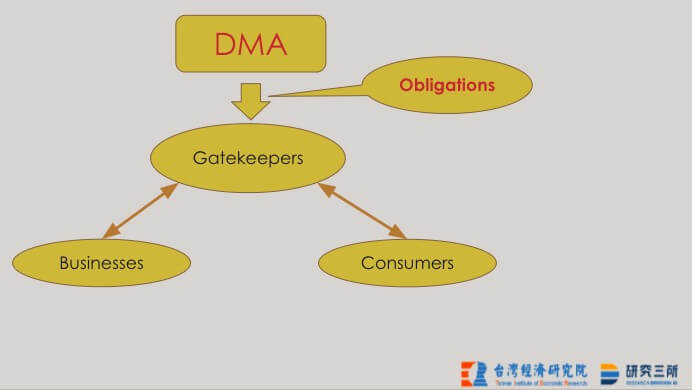

the company will then qualify as a gatekeeper and will have to comply with a set of rules in their daily operations. The DMA is special because it not only protects end-users and consumers but also the small and medium businesses that reply on the gatekeeper platforms to offer their services. In short, we can draw up the basic structure of the DMA as below:

While DMA might be a good example of an ex-ante attempt of asking the Big Tech to behave, Lin reminds the audience to learn about this proposal in its context; the EU has a comprehensive, EU-wide digital market strategic plan in place, and it is a single market with economic significance, which makes its regulation enforceable to the global enterprises.

Lin concluded the introduction by pointing out 2 characteristics of the DMA and stressed that these should be the main takeaways of the proposal. Firstly, EU provides a clear and elaborative rationale for the ex-ante regulation. Secondly, the proposal only was published after multiple rounds of public consultations, independent analysis, and comprehensive impact assessment.

Hao-Chun Tai (Associate Professor of Graduate School of Intellectual Property and Communication Technology, Shih Hsin University) was the first panelist. He shared several cases of Big Tech facing legal controversies in the past few years. In 2017, the EU fined Google €2.42bn (£2.14bn) for abusing its dominance of the search engine market in building its online shopping service. Not only the amount of the fine was record-breaking, but the decision also had far-reaching implications for the Silicon giant.

In June 2020, the Federal Supreme Court of Germany upheld the 2019 decision of the Federal Cartel Office against Facebook during interim proceedings. It preliminarily confirmed that Facebook abused its dominance on Germany’s national market for social networks for private users to the detriment of its users, overruling a preceding decision of the Düsseldorf Court of Appeal. What the ruling meant, basically, was that Facebook has to stop collecting user data without their consent when they are using apps and visiting websites outside the social network.

These were just a few examples of how the Tech Giants abuse their dominance of the market to continuously gain unreasonable advantages over their competitors, making themselves ever-undefeatable. Tai argued that the ‘disruptive innovation’ theory no longer rings true because the Big Tech while becoming big by being innovative in the past, are now disrupting innovation because they are more motivated to stay big and make money. One of the methods Big Tech utilizes is “killer acquisitions”, where they bought startups with extraordinary innovation and took the invention as their own.

Tai echoed what Lin has pointed out in his introduction, that DMA is not based on the anti-competition idea of antitrust legislation but an effort to establish a set of ax ante rules for business compliance. Antitrust is a tough nut to crack when dealing with the Big Tech; in order to enforce antitrust measures, the administration has to first define the market scope. However, with the tech giant’s global operational scale, it would be extremely difficult to scope the market and the whole process may take ages.

The moderator started the panel discussion by asking all panelists to share their thoughts on DMA and if they see DMA as the appropriate way of regulating Big Tech.

Dr. Hung-Hao Chang (Department of Agricultural Economics at National Taiwan University (NTU), former commissioner of Taiwan Fair Trade Committee) thought that DMA sent a strong signal, rectifying data as a critical facility in the digital age. He also praised DMA’s emphasis on innovation. Like what Lin and Tai suggested, DMA sought to regulate the Big Tech with a different approach. While DMA’s move away from antitrust legislation is interesting, Chang said it was still too early to tell how effective DMA can be.

Lin stressed that DMA is a part of the EU Commission’s comprehensive strategic plan of shaping Europe’s digital future. In other words, DMA the means to realize the EU’s strategic objective and not just a regulation for regulation’s sake. Since antitrust measures can take ages before Big Tech started following the rules, Lin said the EU’s choice to go with DMA was a calculated result of probably several cost-benefit analyses. In the context of Taiwan, whether the Fair Trade Committee in Taiwan can enforce antitrust measures on Big Tech is doubtful. However, this does not mean Taiwan should copy and implement DMA as it was. We should analyze the cost and benefit of any regulating approach in the Taiwanese context before putting up such proposals.

Coming from a mass communication background, Hui-Ju Tsai (Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication at Tamkang University) shared her viewpoints from a communication/cultural analysis angle. She urged us to see DMA not as a mere regulation but an attempt to re-direct the Big Tech to the path where they started. The Big Tech became big because of their fundamental values: open and innovation; however, in recent years, we have seen the tech giants deviating from their principle. Even worse, some of them have been actively sabotaging innovation for their own sake of keeping the incompatible advantage in the market.

Tsai argued that we have to take both DSA and DMA into account when analyzing EU’s digital package. She saw this package as a way to shepherd the industry back to human-centered technology evolution. Only when we are putting human beings at the center of any technology development can we protect the human society democratic and open.

DMA might be a promising way of keeping a rein on the big tech, but, Tai noted, EU is very different from Taiwan. EU is a big market—encompassing 27 member states—with strong buying power, not to mention its global status both historically and politically. Taiwan does not enjoy the same privilege. We have to consider the distinction between EU and Taiwan thoroughly before start drafting any similar local regulations.

The moderator followed up with another question: who exactly will be benefitting from DMA? Is it EU? The consumer? Or the small business DMA claims to protect? How can Taiwan learn from DMA

Although DMA only sets out the defining criteria for the ‘gatekeeper’ platforms, it is apparent those who qualify are mostly the global tech companies based in the United States. The US government did push back, claiming DMA discriminative against the American companies. The administration also said the measure is only going to hurt the business in the EU harder than helping them. The US’s response illustrated, Tsai noted, that even for a global power such as the EU to put forward such regulations risks heating international tension.

From a mass communication perspective, Tsai regarded DMA as an approach to return the power to the users and hold the Big Tech accountable. She stressed, however, that DMA (or DSA) still cannot solve the problems public communication is facing, for example, the prevalence of fake news and disinformation. Over-the-top (OTT) media services and platforms of user-generated content are out of DMA’s reach while being one of the primary sources of disinformation.

Lin agreed with the problems Tsai pointed out but suggested that National Communication Committee (NCC) could be a good starting point to address these issues. Before moving to full-on regulation, Lin suggested, NCC can start with drafting operating principles. He added that the process of principle drafting should be open and transparent, taking all stakeholders into account. It is also crucial that the Taiwanese government support the local industry; only when the Taiwanese business can compete with international rivalries on the same footing can we have more bargaining chips on the global negotiation table.

DMA forbids the gatekeepers to withhold data they gather from the third party and use it to their advantage. Chang thought this is a positive move to open data, but he was also concerned about the possibility of companies transferring the cost of DMA compliance to their customers.

The moderators’ final question was ‘is antitrust regulations the best solution for handling Big Tech?’

Tai cautioned against the ‘one solution for all’ way of thinking. The root cause for every event varies, and it is dangerous to look for a “cure-all” for convenience’s sake. Legislation might be the ultimate means, but should not be the ‘only’ means to the end. There are many measures, administrative approaches, consumer choices, just to name a few. Even when we are considering legislation, antitrust would not be the only weapon at the government’s disposal. The industry legislation can also be helpful when enforcing best practices. Tsai agreed that regulation is not the only way. She noted that the Taiwanese community must watch closely how other countries fight their war against the Big Tech. We have to keep in mind that the DMA did not come out of a vacuum but was a cumulated result of years of struggle of the states to contain the global tech giants. It is crucial for us to stand up and speak against the exploitive ways of the Big Tech. We will never stand a chance to win if we never spoke up.